The EBO-SURSY Project is proud to celebrate the International Day of Women and Girls in Science on February 11, which is an annual day of recognition for the contributions of women, both past and present, towards the field of science. The project, whose mission is to strengthen national and regional early detection systems for wildlife and prevent future pandemics, works with and supports the training of a variety of female scientists, laboratory researchers, and veterinarians.

Hosanna Leadisaelle Lenguiya and Linda Bohou Kombila are researchers specialized in emerging diseases in Africa, including the viral hemorrhagic fevers that are a centerpiece of the EBO-SURSY Project. Both women were scholarship recipients of the project as they embarked on their Ph.D. research programs focused on emerging diseases. According to UN Women, just 30 per cent of researchers worldwide today are women, and only 35 per cent of all students enrolled in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) are women. Promoting the empowerment and professional growth of female scientists in its scholarship program, EBO-SURSY values the diversity of its scientists.

Diversity in science is more important than ever as the Covid-19 epidemic has affected women and men of all cultures, and will require new commitments towards research that will help us better understand Covid-19 origins and effects on all lifeforms. Hosanna herself is no stranger to this type of research. She studies the introduction risk of SARS-CoV-2 and the circulation of coronavirus in Congolese wildlife, a topic that she chose because of her passion for studying emerging disease. As the world still endures the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, Hosanna sees her vocation as a way to contribute “by supporting the different aspects of the control response, or even the prevention of these emerging infectious diseases”.

Figure 1: Hosanna holds a hammer headed bat during a routine sampling. During the sampling a bat is measured, weighed, and its biological samples are taken for later lab analysis. IRD © P.Becquart 2019

A native of the Republic of the Congo, Hosanna has a Master in Molecular Biology and Immunology at Université Marien Ngouabi in Brazzaville, where she is also completing the second year of her Ph.D. thesis in virology. She learned about the EBO-SURSY Project when it held a workshop in her university on the risks of emerging diseases. Soon enough she was accepted into the scholarship program and joined a multidisciplinary and international team to manage the sampling and analysis of biological samples taken from wild animals, such as bats. The sampling of wild animals for VHFs can act as an advanced warning system for human health under the principle of One Health; the appearance of diseases in the environment or animals around us can signal an oncoming zoonotic threat to humans.

Figure 2 Hosanna detaches bat caught in a net for the purpose of sampling from Gabon. IRD © P.Becquart 2019

Hosanna’s work adds to efforts to develop a wildlife surveillance system to help prevent future pandemics. However, while Hosanna is passionate about the study of emerging diseases and science, she has not always received the support in her community. “From time to time, I was confronted by those around me” she says, “with judgement saying that women do not have to study as much because they can rely on their beauty”. Others told her that sticking to scientific research would cost her social life . Yet despite these remarks and judgements, Hosanna stuck to studying. She has established a successful career, gaining both experience and a network within the EBO-SURSY Project and its partner Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD). Furthermore, she has become a fully integrated member of the Republic of Congo’s National Laboratory of Public Health (LNSP) where she collaborates and receives training with researchers who work there.

Figure 3 Linda works with a local community to sample goats, which she will later test in the laboratory for diseases such as Ebola or coronaviruses. IRD © P.Becquart 2019

Linda Bohou Kombila, another scientist and doctoral student on the EBO-SURSY Project, similarly benefits from this network with international reach. She studies the implication of domestic animals in the diffusion of pathogen agents and its consequences for human health. Especially interested in zoonotic diseases, her research includes how domestic animals are involved in the chain of transmission from wild animals to humans for specific disease. She documents cases of Rift Valley Fever, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, the rabies virus and the Orf virus in variety of species found in Gabon. While she is currently a doctorale student in the Ecole Doctorale Régionale d’Afrique Centrale Infectiologie Tropicale in Gabon focusing on biomedical studies, she also partners with the Centre Interdisciplinaire de Recherches Médicales de Franceville (CIRMF). With the support of the CIRMF she is able to conduct biomolecular diagnostic testing on wild and domestic animals samples taken from of over 1100 animals as a part of the EBO-SURSY Project.

Figure 4 Linda organises samples taken from her recent field trip to study zoonotic diseases in domesticated animals. IRD © P.Becquart 2019

Linda is at heart an agronomy engineer specialised in animal production, a line of study she followed at the Université des Sciences et Techniques de Masuku in Gabon. Studying engineering as a young women was no easy task. The gender balance of both teachers and students was skewed heavily male, due to cultural and physical expectations in animal production relating to activities such as the slaughtering and castration of animals for food production. In order to be taken seriously, she had to leave any trace of femininity at home and “work like the boys” she recounts. Yet despite her serious dedication to her studies, “there were always some tasks that the teachers would never give to girls due to their physique”.

Not letting this discourage her, Linda went on to complete a Master of Biotechnology and Animal Productions which focused on animal health and physiology at the Université de Dschang in Cameroon. Her cross-disciplinary education encouraged her to think critically about the health of both animals and humans, and the vulnerability of societies to infectious disease threats that spread across borders. Her studies and work on the project have enlarged her perspective to the cost of animal diseases on human public health. She reflects that “the EBO-SURSY Project, with its different field missions and trainings, equipped her with the skills and knowledge on the impact of emerging disease on public health [and] the necessity to put into place a surveillance system for zoonoses”.

A surveillance system for zoonotic diseases requires participation from local communities, who can be the first to identify sick or dead animals in the environments where humans live alongside wildlife. When asked about their favourite activities on the EBO-SURSY Project, both women did not hesitate to say working directly with communities. For Linda, interacting with a community is vital, the participation of the owners of domestic animals during a sampling is essential to her research. Without it, scientists would have much less access to farm animals or herds of goats and duikers, and therefore much less data. Without the data, it would be hard to predict what diseases to anticipate.

Hosanna, on the other hand, enjoyed working directly with the community to raise awareness on disease risk. By presenting scientific evidence and health information on different viruses known to a region, it allowed for each community to develop their own strategies to address them. For example, having sensitised a community on Ebola, community members are empowered to develop a strategy for contacting local health or veterinary authorities when a dead animal, with no apparent cause of death, is spotted by local hunters or found in the vicinity.

Figure 5. Linda meets with the community in Ibomg, Gabon to raise awareness on zoonosis using EBO-SURSY Project tools for hemorrhagic fevers. IRD © P.Becquart 2019

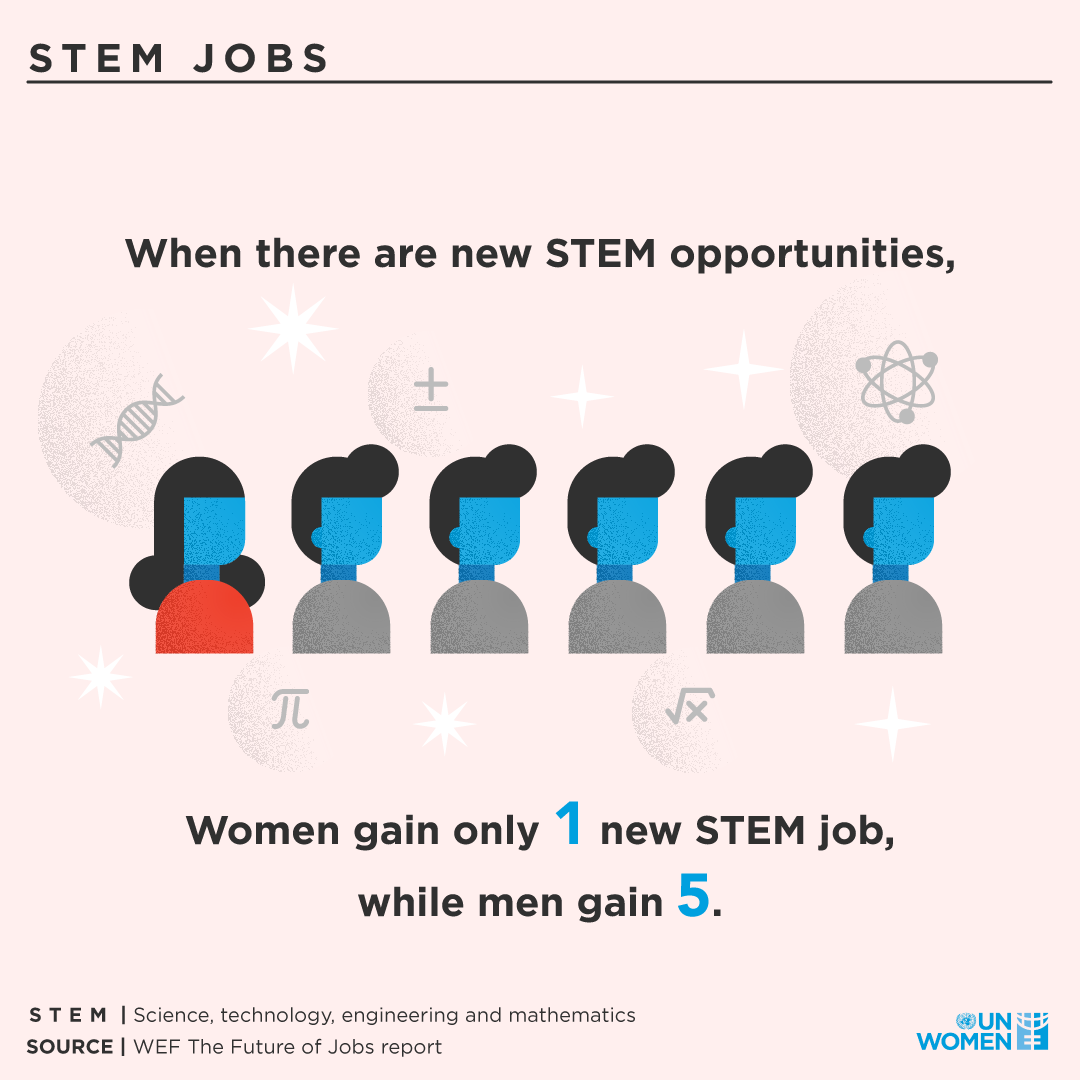

In 2020, the World Economic Forum, reported when there are new job opportunities in STEM sectors, only one woman will benefit from such an opportunity for every five men.

However, promoting the voice and perspective of women in science remains clear. By ensuring women have the same access as men to STEM education and careers, a more diverse and innovative pool of professionals can better solve global problems. Including the prevention of future pandemics.

Linda and Hosanna are still finishing their doctoral programs and looking towards the future. Both are very passionate about pursuing research on emerging diseases after their studies end. Linda aims to establish herself at l’Université des Sciences et Techniques de Masuku au Gabon in a research and teaching position, where she hopes she continue her own research on domesticated animals, while also teaching a new generation of aspiring scientists.

Teaching the next generation of young women interested in STEM is crucial. As female scientists, such as Linda and Hosanna, establish their own careers in the sciences, they represent a new generation of role models for young girls aspiring to do the same.

Figure 6 Linda (left) and Hosanna (right) work together to gently untangle a bat caught in a net for the purpose of sampling in Gabon. IRD © P.Becquart 2019

As such, they have some advice. Linda tells young girls who wish to study science to “set the goals you wish to accomplish. Once you have a dream or a goal in mind, with a strong ‘iron will’, you can achieve your goals”. She goes on to say that occasional failures or mistakes are part of the process. They are necessary in allowing a student to understand their own shortcomings or limits, and how to better overcome them.

Hosanna agrees, and adds:“ To all the girls who wish to study science: they should not focus too much on the difficulty of the questions that remain to be solved. Rather they need to imagine what they could offer if they commit to the study of science… afterall, success is nothing but the fruit of one’s labour!”

Figure 7 Hosanna (left) and Linda (right) working together in Gabon on a field sampling visit. IRD © P.Becquart 2019

READ MORE: visit the EBO-SURSY Project website

[1] With the financial support of the European Union, the OIE-led EBO-SURSY project implemented in coordination with CIRAD, IRD and the Institut Pasteur, aims to reinforce the capacity of national Veterinary Services in ten West and Central African countries to monitor and respond to the Ebola virus as well as four other haemorrhagic fevers – Marburg virus disease, Rift Valley Fever, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, and Lassa fever. These five illnesses are zoonoses or diseases that can spread from animals to humans.