The designations and denominations employed and the presentation of the material in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the OIE concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. The views expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the author(s). The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by the OIE in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.

11 Nov. 2018

Colonel Colonel Musgrave was drinking his coffee in the handsome salon of the merchant, Van Mopez; he opened a pink official telegram and read: — Director of Commissariat to Colonel Musgrave — Marseilles Indian Depot overcrowded meet special train 1000 goats with native goatherds find suitable quarters and organize temporary farm —.

‘Damn the goats!’ he said. His job being to feed Australians, he thought it hard that he had to bear in addition the consequences of the religious laws of the Hindoos (…)

[Arriving at the farm] the colonel went straight to the point: ‘What’s this damned letter that you sent me this morning? You received a thousand goats; you sent me four hundred of them. Show me the others.’ The ground behind the farm sloped gently down to a wooded valley; it was planted with apple-trees (…) A horrible smell arose from the valley, and, coming nearer, the colonel saw about a hundred swollen and rotting carcases of goats scattered about the enclosure (…)

‘Could not one,’ suggested Aurelle on the return journey, ‘ask the advice of a competent man? Perhaps goats cannot stand sleeping out of doors in this damp climate’ (…)

They had begun to build the huts described by the man from the South [South Africa], when the Indian Corps wrote to Colonel Musgrave that they had discovered a British expert whom they were sending him.

[Lieutenant Honeysuckle] was an artillery officer, but goats filled his life. Aurelle (…) found out that he regarded everything in nature from the point of view of a goat. A Gothic cathedral, according to him, was a poor shelter for goats; not enough air, but that could be remedied by breaking the windows.

His first advice was to mix molasses with the fodder which was given to the animals. It was supposed to fatten them and cure them of that distinguished melancholy (…). Large bowls of molasses were therefore distributed to the Hindoo shepherds. The goats remained thin and sad, but the shepherds grew fat. These results surprised the expert.

Then he was shown the plans of the huts. He was astounded. ‘If there is one thing in the world that goats cannot do without,’ he said, ‘it is air. They must have very lofty stables with large windows.’

Colonel Musgrave asked him no more. He thanked him with extreme politeness, then sent for Aurelle. ‘Now listen to me,’ he said: ‘you know Lieutenant Honeysuckle, the goat expert? Well, I never wish to see him again. I order you to go and [look for] a new farm with him. I forbid you to find it. If you can manage to drown him, to run over him with my car, or to get him eaten by the goats, I will recommend you for the Military Cross. If he re-appears here before my huts are finished, I will have you shot. Be off!’

A week later Lieutenant Honeysuckle broke his leg by falling off his horse in a farm-yard. (…) As for the goats, one fine day they stopped dying, and no one ever found out why …

André Maurois, 1918 (translated from the French by Thurfrida Wake)

FIG. 1. MILITARY BLACKSMITHS (BELGIUM). UNCREDITED. (8)

The above excerpts from André Maurois’ 1918 novel, The Silence of Colonel Bramble (24) illustrate the not-so-enviable reputation of the veterinary profession in the early years of the 20th century, initially focused almost entirely on horses. Glorified blacksmiths at best, immoral quacks at worst.

In much of Europe, blacksmiths were indeed most often entrusted with the care of army horses, the main supplier of ‘horse-power’ at the time. Only in 1908 did the Ministry of Finance of the Prussian Empire decide – in principle – to agree to the establishment of a Veterinary Corps, a measure that, due to the economic crisis at the time (which led to the First World War) [Box 1] was only implemented in February 1910.

________________________________________

The initiative included the design of a veterinary military uniform, triggering a relentless wave of mockery by career officers and members of the military Medical Corps, who could not imagine such ‘butchers’ deserving their own Corps.

Despite the four years that separated the establishment of the new Veterinary Corps from the beginning of the First World War, the Corps was painfully unprepared for what was to come, perhaps because of the fact that it was not really taken seriously by the military hierarchy. But it is also true that, both in the Allied camp and in the Central Powers’ camp, the War was not expected to last for more than a few months, enabling the steady supply of animals (and animal feed) from available stocks.

On the German side, three months into the mobilisation, stocks of oats had already run out. On the French side, an 1894 directive had established that the daily ration of a (military) horse should consist of 5.5 kg of oats, 3.5 kg of hay and 2 kg of straw; but also that: ‘in principle, the cavalry must almost exclusively rely on what the land has to offer, to be able to feed the horses on the spot’. Fine, as long as the troops were on the move, but by November 1914 the Front Lines had been stabilised and ‘what the land has to offer’ was depleted within weeks. As a result, the daily hay ration was immediately reduced to 2.5 kg, then to 2 kg in August 1916 and to 1 kg in spring 1917. This also indirectly led to more cases of colic, adding insult to injury. (25)

Over all, the contribution of the Veterinary Corps to the mobilisation of the troops and its potential to assist in the rapid deployment of military personnel and supplies (including animals) had been grossly underestimated. (14, 31)

In Germany, early directives did not take into account the deployment of veterinarians according to their specialties (surgery, internal medicine, bacteriology). The medical equipment provided to the German Veterinary Corps was utterly inadequate and the concept of veterinary hospitals (Pferdelazaretten), despite experience acquired in other military campaigns earlier that century (against the French, the Chinese, and in South-West Africa, now Namibia), was overlooked. Germany entered the War with no army veterinary hospitals. (19) All this was only rectified in 1915, well into the second year of combat. By War’s end, the Germans could rely on 478 of such hospitals, capable of meeting around 20% of their needs.

G. BAUER, DRESDEN MILITARY HISTORICAL MUSEUM. (31)

The French, who were also anticipating a ‘short and sweet’ military counteroffensive, never considered the need to shelter their animals. With winter fast approaching, this was a dangerous omission to make. Following the British example, 4,000 mobile, removable stables were commissioned in 1917, but had only been partially deployed by the time the War ended, leaving the horses and their caretakers to fend for themselves most of the time, by any and all means available. Veterinary care camps (dépôts de chevaux malades or DCMs) were avoided at all costs as they were seen – rightfully so – as distribution centres for diseases and infestations such as mange. (25)

At the onset of the War, on 1 August 1914, the German Army Veterinary Corps employed 766 active veterinarians and 1,507 reservists. Over the four years of the War, 5,354 veterinarians (including those who were drafted) were to take part in military operations, representing some 75% of all veterinarians in Germany at the time. [Box 2] [Box 3] Of these, 241 perished in the fighting. (14, 19)

On the opposing side, on the Western Front in France, the French veterinary contingent consisted of 2,794 veterinarians (72% of all board-certified veterinarians at the time). Of these, between 522 and 546 active veterinary career officers were scattered across the various armies, not in a stand-alone, autonomous Veterinary Corps, but always under the authority of the Cavalry (Direction de la Cavalerie). (13, 20, 25, 26) In peace time, a Cavalry Regiment of between 800 and 1,200 horses would be entitled to a team of three Army veterinarians, the same number as an Artillery Regiment of between 1,100 and 1,500 horses. At the beginning of the War there were 91 Cavalry Regiments and 62 Artillery Regiments. (20)

.

VIDEO “PFERDELAZARETT IN DONCHERRY” (1917) PRODUKTIONSFIRMA BILD- UND FILMAMT (BUFA) (BERLIN). COPYRIGHT: BUNDESARCHIV (2013). THEMA EFG1914 – FILME ZUM 1. WELTKRIEG. FILMPORTAL DEUTSCHLAND.

FIG. 2. GREEN TYPE OF UNIFORMS OF THE VETERINARY CORPS IN THE PRUSSIAN (GERMAN) ARMY (1914 – 1918). SOURCE : BUCHNER, L. (2016) (13)

Of all the veterinarians who joined Army ranks in 1914, only 1,500 actually took part in military operations; the remaining 620 occupied positions in back-up operations, such as warehouses and abattoirs; with 180 being assigned to overseas territories and colonies. (26) Whereas most veterinarians tending to the needs of cavalry horses were regarded as well trained and competent, their numbers were completely insufficient and in fact had been so even before the War. Furthermore, a 1911 Instruction (Directive) assumed that veterinarians in active combat would merely administer immediate care and that horses would then be evacuated to suitable facilities in the towns, or to veterinary care camps (DCMs) established by the Military Command, well behind Front Lines. None of this happened, or at least not immediately. As a result of this assumption, both the standard equipment and medicine cabinets of the typical veterinary support team were primarily geared towards dealing with minor injuries and superficial wounds, an utter mismatch with what veterinarians actually had to deal with.

Over the following months, however, largely thanks to the stabilisation of the Front Lines, things improved and measures were put in place to establish 36 DCMs, with appropriate veterinary professional and para-professional staffing, capable of caring for 25,000 animals. But the battles of the Somme and Verdun, in 1916, annihilated this achievement and soon the number of evacuated horses exceeded 40,000. This led in 1917 to a remarkable overhaul of the DCM system into genuine veterinary hospitals (Hôpitaux vétérinaires aux Armées or HVAs) and to better planning for the provision of substitute horses from behind Front Lines to support the efforts of the Cavalry at the Front. Moreover, extended authority and autonomy were given to the Army’s veterinary professionals, leading – by the time the War ended – to a fully fledged Military Veterinary Service. (13, 25, 26)

While detailed information on the status of the British veterinary contingent is hard to come by, a small group of British benefactors, calling themselves ‘Our Dumb Friends’ League’ (‘dumb’ in the sense of ‘mute’), which had previously been active in the care and protection of working horses in London and other major British cities, entered the scene, establishing ten horse hospitals (and later three dog hospitals) in France.

At the height of the War, more than 80 volunteer veterinarians (and 150 assigned French soldiers) were working for the League under the banner of (the Society of) the ‘Blue Cross’, a term first coined in the Balkan War of 1912 to distinguish its stocks and facilities from those of the Red Cross.

The Blue Cross worked as an ancillary workforce to the French Army, which accepted the League’s offer of support in 1914 with gratitude. Less so the British forces, which initially declined the League’s offer of help, having recently established a ‘proper’ Military Veterinary Corps. However, this was to change later on in the War.

Although the numerical contribution of the Blue Cross, in terms of hospitals, workforce and animals in its care, remained relatively modest (6,058 horses over the four years of the War), its most valued contribution lay in the fact that it established new, high standards of care, which were eventually adopted by the Military Veterinary Corps as a whole, and by the DCMs in France, mentioned above.

In 1915, the Blue Cross extended its offer to Italy. By the end of October 1915, six hospitals had been established and 1,872 horses taken into care. (32) A Military Veterinary Academy (Scuola del Servizio Veterinario Militare) had already been established in Italy in 1796, by Carlo Emanuele III di Savoia in Venaria Reale (today, a suburb of Turin). From 219 veterinary officers in 1915, numbers increased more than tenfold to 2,819 military veterinarians in 1918. Thirty-nine veterinarians never made it back home. Over the course of the War, 600,000 surgeries were conducted on four-footers (equids, large ruminants and dogs); 260,000 animals were treated in veterinary facilities and the total number of casualties was estimated at 76,000 or 21%, a relatively low mortality rate compared to the losses on the French and British side. (22, 30)

Belgium, which had adopted a neutral role in the emerging conflict, was nonetheless invaded by German troops one day after Germany declared war on France. At that time, Belgium had a Veterinary Corps consisting of a mere 48 career veterinary officers. [Box 4] Shortly afterwards, this grew to 160 ‘volunteers’ (8) in the little that was left of Unoccupied Belgium, a small enclave abutting France and surrounding the town of Ypres, a town which would, in later years, gain worldwide notoriety, like other hitherto unknown places, such as Verdun, Passchendaele or Gallipoli, during the same period, and for the same gruesome reasons…

VIDEO “WAR HORSE ON STAGE”, CENTER THEATRE GROUP (POSTED IN JUNE 2012).

The 1982 Michael Morpurgo novel for young adults, War Horse (28), later turned into a compelling play using ground-breaking puppetry techniques and an award-winning movie of the same name by Steven Spielberg in 2012, has made a global audience aware of the realities of being a war horse.

VIDEO (OFFICIAL TRAILER) “WAR HORSE” (DREAMWORKS PICTURES, 2011)

When it came to horses and mules, both sides of the conflict seem to have had to deal with the same scourges. Though reliable statistics are not available for the early years of the War, reporting systems were eventually put in place, allowing for a better understanding of what pathologies and metabolic disorders filled the army veterinarian’s working day. (19)

To fully appreciate this, a clear distinction must be made between mobilisation and military campaigns into enemy territory (marches) to establish a Front Line, and the protracted later stages of the War – at least in Europe – a War which was fought in the trenches and characterised by the immobility of the (Western) Front.

On the Eastern and Southern Fronts, both sides remained on the move for the greater part of the War.

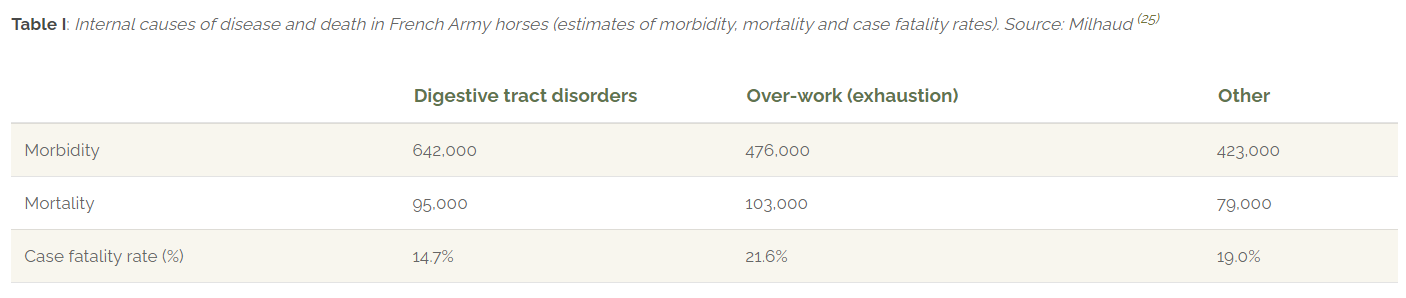

When veterinarians are accompanying these campaigns, following a few kilometres behind the military columns, they have to deal with piercing wounds (from barbed wire, sabres, bayonets, bullets, shrapnel from exploded grenades or shells), lameness and pressure wounds from saddles and gear. (14, 19, 31) The latter, especially in summertime, are often further compounded by respiratory distress due to the inhalation of dust and gunpowder, while winter brings colds due to inadequate shelter against the rain and cold weather. Much lameness is due to penetrating nails, which have come off the wooden wheels of wagons, carts and gun carriages. In addition, chronic malnutrition, lack of quality roughage, lack of water and insufficient rest are widely held responsible for intestinal tract disorders, such as colic (Table I). (14, 19, 25)

Let it be clear that there were limits to the extent of veterinary care of horses. Many ended up being abandoned, left behind, or – if they were lucky – shot. One source (10) stated that the average shelf-life of a war horse was a mere five weeks.

As the War came to a stalemate in the trenches, the initial response of soldier and animal was relief: no more pulling heavy loads, shorter response times, faster supply of medicines, sufficient rest, and time for rehabilitation, better shelters…

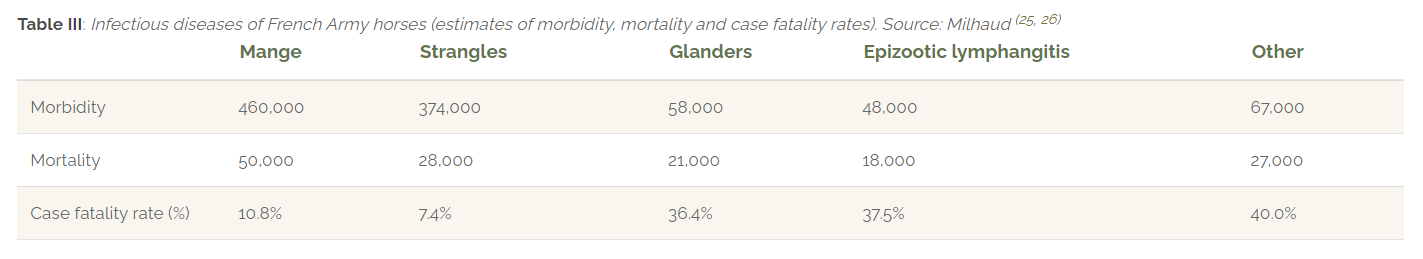

While this was of course true, the mass concentration of animals in a small area, in unhygienic conditions, and the lack of proper food supplies from behind Front Lines also led to an increase in infectious diseases and infestations, many of which are rarely heard of today (Table II).

One of the diseases which flared up at march’s end, at least on the German side, was Brustseuche or Pleuropneumonia contagiosa equorum, a disease for which a successful arsenic-based treatment had been developed in 1911, Salvarsans® (Arsphenamine), but which had been overlooked in the arsenal of veterinary drugs. Only when Salvarsans® was widely applied, from 1916 onwards, did the disease come under control. (19)

Strangles, if antibiotics had been available at the time, would scarcely have rated a mention in the list. Unfortunately, penicillin was not discovered until 1928, leaving scores of horses to succumb to the upper respiratory tract infections of Streptococcus equi (or Coryza contagiosa equorum). (19)

Bousquet and Giard (13) report that, in the French camp in 1918, 155,000 horses were affected by mange, which seems to be in line with the statistic by Milhaud (25) over the four years of the conflict (Table III). As a preventative measure, the British Army resorted to shaving its horses, although this backfired at the onset of winter, when they frequently succumbed to hypothermia. (10) The Blue Cross reportedly cured 10,000 horses of mange, using sulphur baths. (32) The development of the sulphur dioxide gas treatment, which occurred almost simultaneously in France, England and Germany towards the end of the War, came too late to be of any use. (19)

While the Institut Pasteur finalised the development of a rudimentary vaccine against glanders (and melioidosis, the human variant, caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei), based on killed malleine, there were still 32,000 animal cases reported in 1915 alone. (13) Some of these infections may have been intentional, as glanders is also regarded as one of the first biological weapons used in modern warfare, reportedly employed by the German troops to destabilise the Allied cavalry. (21)

Though precise figures are not available, it would appear that the German army, in addition to running its own stud and breeding farms, guaranteed a continuous supply of horses on the principle that all privately owned horses were regarded as ‘military reservists’, to be drafted as soon as required. To no avail, as the availability of horses and mules soon plummeted when the War lingered on for much longer than expected. (10) Nonetheless, towards the end of the War, by 1917, the German army still found itself with 1.2 million horses on hand. (14, 19)

In Belgium’s armed forces, behind the Yzer Front Line, numbers grew from 20,000 in 1914 to 36,000 towards the summer of 1918. (8) In occupied Belgium, however, more than 110,000 horses were requisitioned by the Occupying Forces over the course of the War.

In 1914, in what was then Great Britain, the Royal Army had a mere 25,000 horses at its disposal , but – thanks to a well-prepared Remount Service, the body responsible for buying and training horses – was able to identify and purchase (with varying degrees of agreement on the part of the owners) between 140,000 and 165,000 horses and mules in a matter of days after the declaration of war on Germany. (10, 32) This enabled Britain to enter the War with the necessary numbers of cavalry and traction animals, but was soon insufficient to maintain the supply. Enter the United States and Canada, but also Argentina. Thanks to extensive breeding of – in particular – mules, in states such as Missouri, Britain was able to import, acclimatise and then transfer to the Front some 429,000 horses and 275,000 mules. (10, 33) The Blue Cross (32) estimates that, by 1917, there were 869,931 horses on active service.

In 1915, when Italy entered the War, the number of draught animals (which likely also included oxen) quickly rose from a mere 800 to 9,000 animals by 1916, to reach 18,000 by the end of the War. (4) In all, between 300,000 and 520,000 mules and 350,000 horses took part in the war effort. (30, 33)

In France, in the first weeks of mobilisation, the Army, which had a standing stock of 175,000 horses (20), requisitioned no fewer than 22,486 mules and 489,743 horses (up to 700,000 (33) horses between August to December 1914). These numbers were so high that there must have been some serious flaws in the selection process, especially since veterinarians were seldom involved in selection by the requisitioning committee (commission de réquisition). (20, 25, 26) This reflected the subordinate status of veterinarians at the time, a status which improved during the War and was finally acknowledged after it ended.[Box 5] Moreover, the fact that young adult men and horses were pulled from farming communities that still relied heavily upon manual labour and animal traction to work their fields (33) must have had a severe impact on food production resulting in widespread malnutrition; consequences that should not be underestimated.

E. DARRE & E. DUMAS (18)

The available information varies but, over the course of the War, the French Army drafted anywhere between 1.88 million (25) and 2.75 million (20) horses and mules. Where authors seem to agree is that 1.14 million of them were killed while on service, a very high mortality rate, even in relation to 2.75 million equids (41%). Most of these animals, of course, were not proper cavalry horses, but draught horses, taken from farms and poorly adapted to the long marches that characterised the first phase of the War. (33) Coincidentally, the mortality rate was the same for the 1,183,228 horses brought into the War by Great Britain, of which 484,000 were killed (41%).

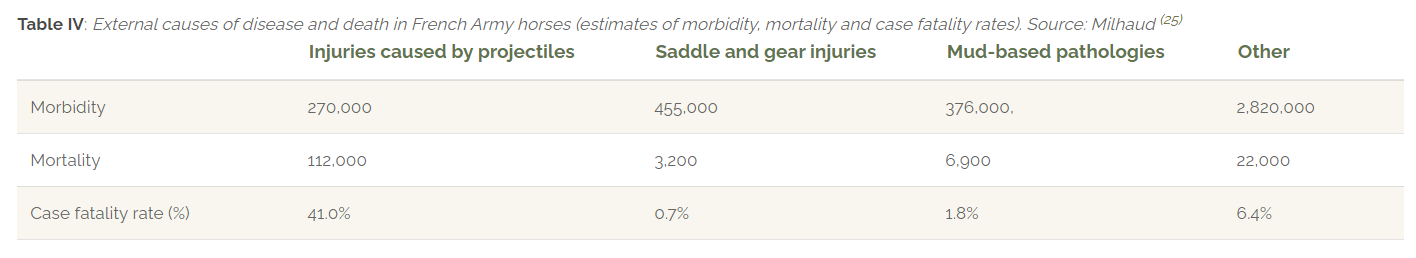

Milhaud (25, 26) points to the extraordinary number of animals suffering and dying from what he refers to as ‘internal’ disorders (Table I), as opposed to ‘external’ disorders, such as ‘mud-related’ injuries but especially bullet wounds (Table IV). Remember, this was the first time that automatic machine guns had been used against the cavalry (22), both from land and air, using the first synchronised machine-gun/propeller (Fokker Aeroplan) warplanes. (31, 33) As early as autumn of 1915, the helplessness of animal against machine led to many of the cavalry regiments being disbanded and converted into infantry. Many of the ‘dismounted’ officers turned to the new Air Force to become pilots; that very Air Force which had signalled the end of their mounted career. (33)

(PARAPHRASED FROM ITALIAN) N. ROMBOLA & A. PUGLIESE. (22)

As a result of the same shortcomings in reporting and collecting data mentioned earlier, reliable numbers of animal casualties (whatever the causes) are hard to come by, and figures are usually rounded to millions for lack of more precise metrics. The most often quoted figure is between six and eight million horses. However roughly estimated (and sometimes considered controversial, because inflated), this is nonetheless a staggering number when compared to human military casualties: ten million, and the overall number of human casualties: 16 – 17 million. (6)

S. VON SCHENCK & R. BEI DER KELLEN. (31)

FIG. 3. “BLUE CROSS” TREATMENT CAMP FOR HORSES. DRAWING BY F. MATANIA FOR SPHERE MAGAZINE N° 788 OF 27 FEBRUARY 1915. REPRODUCED IN: VON DEN DRIESCH AND PETERS, 2003. (18)

FIG. 4. BANDAGING OF A SENTINEL DOG, WOUNDED BY GRANADE SHRAPNEL. DOG SHELTER (“LAZARETT”) BEHIND THE FRONT. PICTURE (C) BILDERDIENST SÜDEUTSCHER VERLAG. IN : VON DEN DRIESCH AND PETERS, 2003. (18)

Having neglected investment and maintenance of operational capacity after the (smaller) wars earlier that century, Germany was able to rely on a mere 6,000 dogs at the beginning of the War. By the time it ended, numbers had grown to 30,000. (14) In France, Thomas (33) claims that 12,000 dogs were ‘sous les armes’ (serving in the Army). Darré and Dumas (18) refer to 15,000 dogs, whereas the Blue Cross (32), which became involved in treating dogs from 1917, put the figure at 18,000 ‘war dogs’ in France. By the end of 1917, the Blue Cross had admitted 1,604 dogs into its veterinary hospitals, and sent back 1,088 cured dogs to active duty. One such patient was a German war dog which strayed into enemy lines, a ‘prisoner of war’ situation not anticipated by the Geneva Convention. By 1919, the Blue Cross reported having taken 10,169 dogs into care, of which 8,586 were returned to the Front, once treated.

It has not been possible to identify sources describing the nature of the injuries and/or pathologies/infectious conditions found in these dogs.

Dogs were used in rescue operations, especially in extreme mountainous environments such as the Alps (+3,000 m, up to -30°C) (3), as conveyors of military information; for pest control in the trenches (rats); as sentinels (or guard dogs); and as police dogs. Rescue dogs, it is believed, were trained to distinguish the wounded from their own camp or army, from those of the opposing camp, who were left to fend for themselves. (33)

Dogs were also used in many countries and armies for animal traction (except in Germany), to transport injured or dead soldiers, or to pull light artillery to the Front. The latter was not a great success and was soon abandoned (in Belgium), as the barking of the dogs turned them into target practice for the opposing artillery. (7, 33)

FIG. 5. STATUE OF “JACK”. THE PLAQUE READS “JACK THE DOG SERVED AS A VERY WORTHY SLEUTH-HOUND FOR THE BRITISH INFANTRY DURING THE 1ST WORLD WAR. IN 1918 HOWEVER, HE WAS KILLED AT THE FRONT NEAR YPRES IN WEST FLANDERS”. THE SURROUNDING DOG-CASTS ARE PART OF THE ONGOING CONTEMPORARY ART BIENNALE “BEAUFORT 2018” IN OSTEND, BELGIUM. PICTURE © IRENE KLIMIS (2018)

The French army used sleigh dogs more successfully. Some 436 were brought in from Alaska in 1915, during the heavy winters in the Vosges mountains, in the North-East of France. (33)

SIR ERNEST FLOWER, CHAIRMAN, BLUE CROSS FUND. (32)

While many dogs died during the War, they were also credited with saving thousands of lives, thanks to their ability to sniff out explosives, landmines and nerve gas attacks. From the spring of 1915, new military tactics were introduced, including the use of mustard gas, which had been strictly prohibited by the Convention of the Hague, signed in 1899.

Gas attacks left not only millions of soldiers and civilians dead or blind, but also an undefined number of animals. Horses and dogs could be equipped with gas masks, while pigeons were protected from gas attacks in special chambers, but many still died. Given the above, the First World War also saw intensified training of dogs to assist the blind. (32)

As was the case with horses and dogs, pigeons would never again be used to such an extent in any war, except maybe in Operation Columba (1941 – 1944), which involved more than 16,000 ‘Allied’ pigeons). (17)

Given their extraordinary homing instinct, pigeons were of course used to relay information across terrestrial Front Lines, hence their ‘rank’ of carrier pigeons or messenger pigeons. But they also ended up serving on warships and even submarines, as back-up for other forms of communication, or being released from ships in case of shipwreck, as well as from aircraft (from which they could be launched in mid-air.(16) Collela (15) argues that pigeons could be ready for operation after only 20 to 25 days of training, using fixed pigeon lofts.

During the War in Italy, on the Tyrol Front, it was absolutely prohibited to shoot, wound or capture pigeons, whatever the animals’ ‘allegiance’. The Italians preferred not to intercept the enemy’s military communications, rather than risk exposing their own. (4)

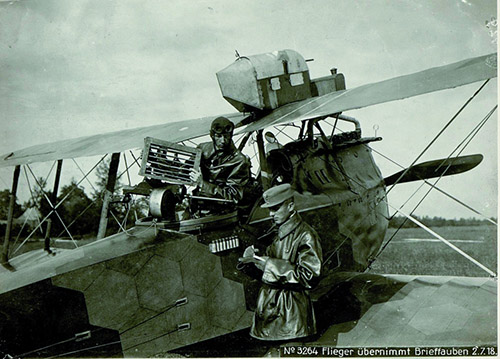

FIG. 6. TRANSPORT OF PIGEONS BY PLANE, PROBABLY VENICE, JULY 1918. PICTURE (C) ÖSTERREICHISCHE NATIONALBIBLIOTHEK (ÖNB). (13)

Similarly, Germany outlawed the possession and use of pigeons by civilians at an early stage, with hefty fines, imprisonment and even the death penalty as deterrents. (33) At the beginning of the War, Germany had some 21,000 ‘military’ homing pigeons, lodged in 30 pigeon lofts along the borders, and at the Western and Eastern Fronts. By the end of the War, these numbers had risen to 120,000 animals and 500 lofts. (14, 19) But other sources claim that the Germans requisitioned up to a million birds from Occupied Belgium, where the sport of pigeon racing was already hugely popular before the War (and still is today). In France, their numbers quickly rose from 1,500 in 1915 to some 60,000 during the War, of which an estimated 20,000 were lost in combat. (33)

In Britain, the Royal Pigeon Racing Association estimated, based on more than 10,000 documents and photographs, that more than 100,000 pigeons served with British forces and that their success rate for getting messages through was approximately 95%, but only in daytime. (16) Unlike the British, the French and Belgians knew that pigeons could be trained to fly at night and their birds managed to pull off some remarkable military exploits. (33)

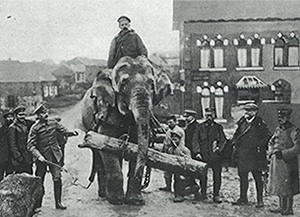

Further afield, the various military factions made use of many other animals, adapted to the environment in which the wars were fought. These included, in addition to mules and donkeys, camels, oxen, water buffalo and so forth. (19) Needless to say, many reports described how foot and mouth disease (FMD) outbreaks ran many an operation using ruminants into the ground. (14) Mules were particularly appreciated on the Southern European (Tyrol) Front, where the famous Alpine mountain infantry (‘chasseurs alpins’ in French or ‘alpini’ in Italian) relied heavily on mules to manoeuvre men and artillery through the inaccessible and inhospitable terrain of the Alps, and especially the Dolomite mountain ranges where other animals – except for dogs – were largely useless. (3, 7, 12) [Box 7]

FIG. 7. AN ELEPHANT BEING PUT TO GOOD USE FOR THE TRANSPORT OF TREE TRUNKS DURING THE WAR IN PERONNE, FRANCE. PICTURE (C) ILLUSTRIERTER KRIEGS KURIER, N° 23, 1915. IN: THOMAS 2018. (32)

A few articles mention the use of falcons (for the same purpose as pigeons) (3) and even bees (as early warning against gas attacks in the trenches of the Western Front). (7) Finally, a few individual animal species made it to ‘mascot’ status, such as the kangaroo which accompanied the Ninth and Tenth Australian Infantry Battalions deep into Egypt, or ‘Buddha’ the monkey, mascot of one of the Belgian Lancers’ squadrons.

Many wild species, including birds and mammals such as foxes (manageable once tame), and rats (more problematic, due to their lice and fleas), adapted to human companionship and ended up living in the trenches, alongside soldiers, for the same reasons soldiers did: refuge. (33)

All species considered, the War effort mobilised some 14 million animals, 10 million of which were equids. (33)

Most references to the role of veterinarians were made in respect to their role in treating these animals who had (‘who’ is used on purpose) fallen victim to enemy fire in the line of duty, whether this was to carry an officer, pull a cannon, rescue a wounded soldier or deliver a message.

Much less is known about the role of veterinarians in the safety of food supplied to the troops. The quotes from The Silence of Colonel Bramble, with which this article started, point to the challenges in regard to food supply, both in terms of quantity and in terms of quality, safety and hygiene. . The Belgian 1914−1918 memorial website states that ‘veterinarians dedicated much of their work to preventative animal care. They advised the hierarchy on the purchase, lodging, feeding and use of animals. They were responsible for the staff training of the veterinary infirmaries and the farriers. They also carried out hygiene control work in bakeries and military slaughterhouses’. (8)

Much less is known about the role of veterinarians in the safety of food supplied to the troops. The quotes from The Silence of Colonel Bramble, with which this article started, point to the challenges in regard to food supply, both in terms of quantity and in terms of quality, safety and hygiene. . The Belgian 1914−1918 memorial website states that ‘veterinarians dedicated much of their work to preventative animal care. They advised the hierarchy on the purchase, lodging, feeding and use of animals. They were responsible for the staff training of the veterinary infirmaries and the farriers. They also carried out hygiene control work in bakeries and military slaughterhouses’. (8)

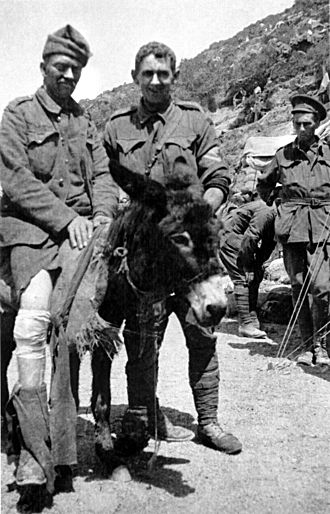

FIG. 8. JACK SIMPSON KIRKPATRICK (CENTRE) WITH HIS DONKEY, BEARING A WOUNDED SOLDIER. (11) IN ACTUAL FACT SIMPSON USED AT LEAST FIVE DIFFERENT DONKEYS, KNOWN AS “DUFFY NO. 1”, “DUFFY NO. 2”, “MURPHY”, “QUEEN ELIZABETH” AND “ABDUL” AT GALLIPOLI; SOME OF THE DONKEYS WERE KILLED AND/OR WOUNDED IN ACTION.

In France, Pasteur’s discoveries in the late 19th century had elucidated the role of micro-organisms in several diseases and the risks involved in the consumption of contaminated food. Whereas meat inspection in abattoirs was soon entrusted to city councils (municipalités), meat inspection for the troops was entrusted to Army veterinarians and soon extended to include all foodstuffs and all aspects of food hygiene in mass catering. (18) Milhaud (25) nonetheless found that only 10% of the estimated 1,500 ‘field’ veterinarians serving in the Army were actually entrusted with the food supply; that is, sanitary surveillance of livestock markets and feedlots, and meat inspection in the Army abattoirs. These veterinarians focused not only on ensuring the daily supply of 450 grams of meat per soldier, but also in dealing with outbreaks of FMD before slaughter and the destruction of tuberculosis-ridden carcasses post-slaughter.

From 1916 onwards, faced with challenges in the provision of meat (including frozen meat from colonies as far away as Madagascar), and increasing numbers of culled horses at the Front, part of the meat supply was sourced from these horses and initially supplied to the troops as ‘Arles’ or ‘Lyon’ (with pork) sausages but, later on in the War, as fresh meat. (26) [Box 8]

On the occasion of the centenary of the First World War, remembered across the world from 2014 until the end of 2018, many aspects and experiences of this global conflict have been re-examined or brought to light for the first time, as we honour the memory of those estimated 16 million soldiers and civilians who perished in what was then known as the ‘Great War’, or the ‘War to End All Wars’. So many of these died on the infamous fields of Flanders, where Allied and Central Forces dug themselves into trenches for the better part of four years.

Over the past few years, new research has brought to light many insights into the plight of animals in this War, which – for the younger readers amongst you – was fought at the dawn of motorised warfare, using anything powered by two or four feet or paws, from the homing pigeons delivering secret messages across enemy lines, to the traction provided by oxen and mules to pull cannons and other heavy artillery, to the horses of the cavalry. Not least among these roles was the supply of animal protein to the troops, whether this came through the specific designation of animals for this purpose or as the result of a failed attempt at delivering any of the above services. Several leading publications today have documented the role (and suffering) of animals in ‘La Grande Guerre’.

Less so the role of veterinarians in the ‘War to End All Wars’. Who were they? How many? How were they organised? What did they do, on either side of the enemy lines? The present article is a humble attempt to shed some light on these veterinary colleagues, based on available, mostly grey, literature. The authors make no claims to be comprehensive or scientifically robust. The War was a complex patchwork of combating armies and distrustful alliances, with infantry from as far afield as Senegal (the Tirailleurs sénégalais), India, Australia, New Zealand and Canada, and battles fought in all corners of the world, from the Pacific to South and South-West Africa. What is presented here is, therefore, at best anecdotal, prompted by little more than willingness to remember those colleagues who gave their best for whatever vision of the world they believed in, in the context of their era. Hence, this 11 November 2018, a century after the Armistice, spare a thought for these veterinary colleagues, and for the animals they cared for, because the latter, as so often repeated, ‘had no choice’…(10)

.