Rift Valley Fever is named after the Rift Valley in Kenya and is another truly African disease, which has now spread to the Indian Ocean and parts of the Middle East and the Arabian Peninsula. It is a disease of sheep (mostly), leading to waves of abortions in ewes.

The main concern with Rift Valley Fever is that it is a deadly zoonosis, which can infects farmers, farm labourers, abattoir workers and other animal health professionals (veterinary workforce) through contact with infected secretions and excretions from ewes. Outbreaks in Kenya and Tanzania in 2006, and Somalia in 2007 led to hundreds of casualties.

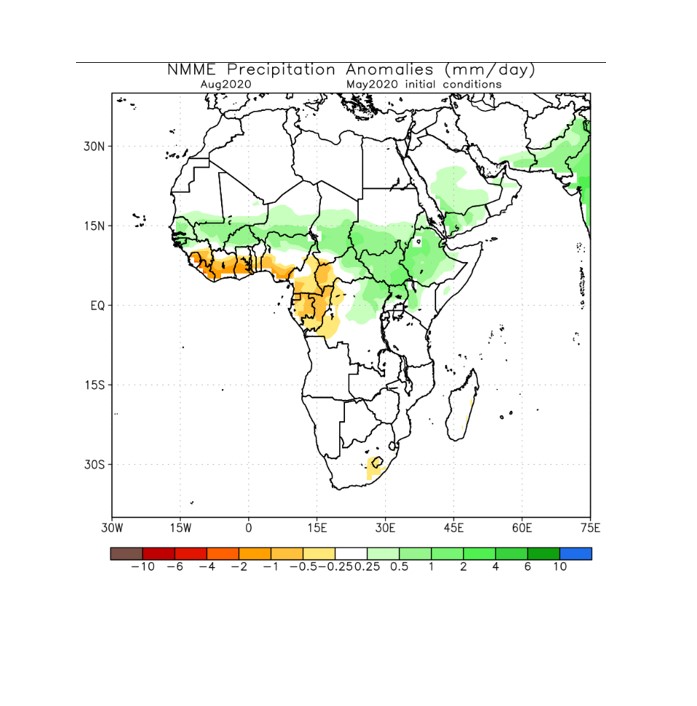

Map: NMME Precipitation anomalies (mm/day) predicted for August 2020 (FAO/ICPALD, May 2020)

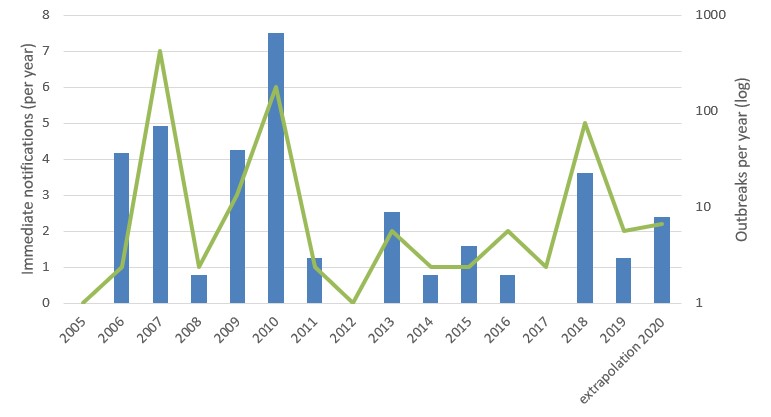

Fig: Annual number of immediate notifications (green lines) and number of outbreaks (blue bars) reported to the (then) OIE from 2005 – 2020 (WAHIS, May 2020)

More recently, in 2009 and 2010, the Republic of South Africa reported close to 500 outbreaks of RVF to the (then) OIE and suffered 18 human losses, amongst which a young lady-veterinarian. In 2010, an unprecedented outbreak of RVF was reported in Mauritania causing loss of human life and killing cattle.

In west Africa, more outbreaks, though relatively reduced in scale, occurred in Mauritania (2013, 2015), Senegal (2013), Niger (2016) and Mali (2017). In eastern Africa, after an inter-epizootic period of some 8 years (2011 – 2017), outbreaks were again reported from 2018 onwards, with immediate notifications being submitted by Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Sudan, and Uganda, in addition to Chad and South Africa (and lately – January 2020 – Libya).

Global warming is likely to lead to a modified and possibly enlarged distribution of the main disease vectors, the Culex and Aedes mosquitos, which has already proven to survive in previously unaffected countries, such as Portugal, Spain and Italy. This threat to the developed world has triggered accelerated research in prevention and control of RVF. Several vaccines for use in animals are available but are not used on a wide scale since RVF outbreaks tend to be unpredictable (but often related to floods) and follow an approximate 10-year cycle. This epidemiological feature also makes the establishment of vaccine banks cost-inefficient, at least with the current set of vaccines. Also, few sufficiently sensitive pen-side tests are widely available.

Above picture (c) S. Glinski (FAO). Top picture (c) S. Maina (FAO)

WOAH Reference Laboratory

Dr Baratang Alison Lubisi

Onderstepoort Veterinary Research

Agricultural Research Council

Private Bag X05

Onderstepoort 0110

SOUTH AFRICATel: +27-12 529 91 17

Email: [email protected]

FAO Reference Centre for technical assistance in quality control of veterinary vaccines

WOAH Collaborating Centre for the quality control of veterinary vaccines

Dr Charles Bodjo

Pan African Veterinary Vaccines Centre (PANVAC)

African Union

P.o.box 1746, Debre Zeit,

ETHIOPIA

Tel: +251 – 11 4338001

Email: [email protected]

Email: [email protected]

FAO Reference Centres for Vectors and Vector-borne diseases in Africa

Dr Sikhumbuzo Mbizeni

Onderstepoort Veterinary Research

Agricultural Research Council

Private Bag X05

Onderstepoort 0110

SOUTH AFRICA

Tel: +27-12 529 91 06

Email: [email protected] et [email protected]

Dr. Abdou Tenkouano

International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe)

Duduville Campus, Off Thika Road,

Kasarani

P.o.box 30772-00100, Nairobi,

KENYA

Tel: +254 20 863 2000

Tel : +254 733 634 366

Email: [email protected] et [email protected]

Dr. Guiguigbaza Kossigan Dayo

Centre International de Recherche-Développement sur l’Elevage en zone Subhumide (CIRDES)

N°559, rue 5-31 av. du Gouverneur Louveau

Bobo-Dioulasso

BURKINA FASO

Tel: +226 20 97 20 53

Tel: +226 20 97 26 38

Email: [email protected]